that I had your glove,

the one I stole in fear and trembling:

then I feared

you would be harmed

by the lady who has your service;

so, friend, at once

I gave it back, because I know

I have no rightful claim.

-Castelloza, “Ia de chanter non degra aver talan”, Matilda Tomaryn Bruckner et al (trans.)

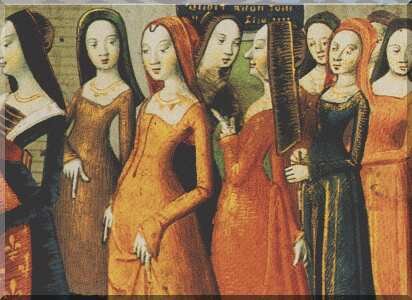

This post springs from some of the reading that I have been doing for my masters, which, as is often the case, resonates in other spaces that I occupy. I have been reading about women troubadours (trobairitz) from the Middle Ages. Only a handful of their writings survive, far less than those of male troubadours. These women write within and outside the tradition of fin’amor, in which the lowly poet begs for the love of a usually silent and distant lady, typically the wife of his lord. What I find interesting about this tradition is that it appears to put the lady in a position of power, during a time in history when you expect that women would have very little power at all. The courtly lady rejects the advances of luckless suitors from her pedestal, seemingly entirely in control. What the lyrics of love and pain obscure from the reader however, is the economic code they represent. Laura A. Finke describes fin’amor as “an ideology that smoothed over the contradictions brought about by homosocial competition to control women as resources… It represented aristocratic women as simultaneously on display and inaccessible” (Feminist theory, women’s writing, 1992). The apparently heartfelt poetry of fin’amor had more to do with economics than the love of women, in effect, the poems operated as coinage, a form of symbolic patronage between vassals and their lords. Thus, “the languages of poetry and of sexual desire existed in a dialogic relationship- entangled- with the languages of economics, warfare, and politics” (Ibid).

When women write within the codes, forms and symbols of this tradition, the results are subversive, exposing the power dynamics and struggles that the poetry was originally designed to hide. In the case of Castelloza, the trobairitz I quoted from above, she does not write from the position of a woman in power, and the effect is unsettling. She tries to write about subjects that the code of fin’amor was not designed for, and so her words, meanings and associations swell against the poem’s form, flooding the retaining wall of language.

This is important to me when I am trying to write the voice of a woman narrator who threatens the retaining walls of courtly discourse in a society where women’s speech is considered irrelevant at best. It is also interesting to think about when I am considering the value of having a voice in other conversations and spaces, particularly in spaces where the accepted discourse is somewhat inaccessible, or challenging. I find myself ‘trying on’ different discourses all the time, particularly in various teaching worlds, until they become comfortable. But then, I start to worry about why they have become comfortable, concerned that they slipped over my body like a soft, faded jumper without me noticing. I worry that I am becoming parrot-like, speaking in shared languages to make connections, even if I don’t truly understand the translation.

And so, the anxiety of mimicry leads me here, to think critically about the discourses that I hide behind, to develop my own critical understanding of them. Then, when I put them on again, I will feel at ease because although I’ll be wearing the same soft, faded jumper, I will be standing in my own doc martins.

Stay tuned.

No comments:

Post a Comment